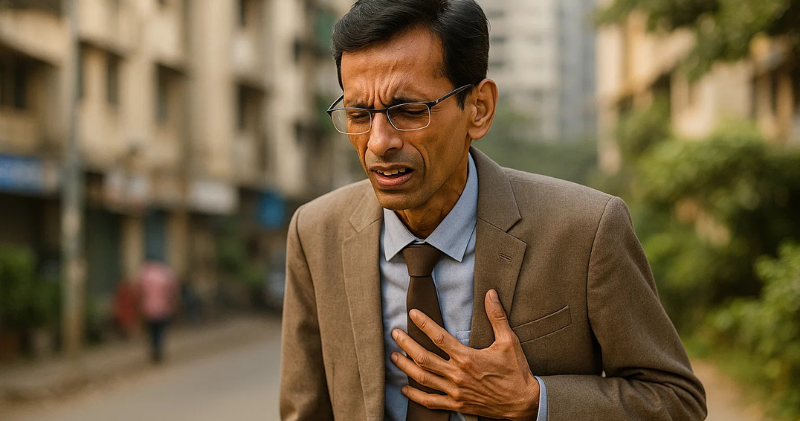

We all have that one relative – the charming uncle who’s been the same slim size since his college days. He walks to the market daily, never misses his evening chai, and proudly tells everyone he’s “never had a weight problem.” He laughs off health concerns because, after all, he looks fit compared to his heavier friends. His family feels relieved too – at least Uncle doesn’t have the obesity issues they read about in health articles.

But here’s a shocking truth that might save his life: being thin doesn’t protect South Asians from heart disease or diabetes. In fact, some of the highest-risk people walking around look perfectly healthy on the outside.

This phenomenon has a name – TOFI, or “Thin Outside, Fat Inside” – and it’s quietly affecting millions of South Asians worldwide. Your skinny uncle in Mumbai, your lean cousin in London, or even you might be carrying dangerous hidden fat around vital organs, setting the stage for a heart attack that no one sees coming.

How can someone look healthy and still be at high risk? The answer lies in understanding what’s happening beneath the surface – and why our traditional understanding of health is dangerously incomplete for South Asian bodies.

The TOFI Phenomenon: When Thin Doesn’t Mean Healthy

TOFI stands for “Thin Outside, Fat Inside,” and it perfectly describes what scientists have discovered about South Asian health. Imagine two apples that look identical from the outside – one crisp and healthy, the other rotting from within. That’s essentially what’s happening in many South Asian bodies.

While the fat you can see (subcutaneous fat) sits harmlessly under your skin, there’s another type called visceral fat that wraps around your internal organs like the liver, pancreas, and heart. This hidden fat is metabolically active, constantly releasing inflammatory chemicals and interfering with normal organ function.

Unlike the fat on your arms or thighs, visceral fat doesn’t show up as love handles or a double chin. You can have a flat stomach and still have dangerous amounts of fat choking your organs. It’s like having a thin person’s body with an obese person’s metabolism – the worst of both worlds.

This explains why so many “healthy-looking” South Asians suddenly develop diabetes, have unexpected heart attacks, or discover they have fatty liver disease during routine checkups. Their bodies have been silently accumulating internal fat for years, even while maintaining a normal weight and appearance.

Why South Asians Are Hit Harder by TOFI

Genetics dealt South Asians a challenging hand when it comes to fat storage and metabolism. Research published in The Lancet shows that people of South Asian descent develop diabetes and heart disease at much lower BMIs than other populations – often at a “normal” BMI of 23-25, compared to 27-30 for Europeans¹.

Our bodies are programmed differently. We tend to have less muscle mass and more internal fat, even when our overall weight looks healthy. This isn’t a character flaw or poor discipline – it’s how our genetics adapted to historical cycles of feast and famine. What once helped our ancestors survive food shortages now works against us in a world of abundant refined carbohydrates and sedentary lifestyles.

The Harvard School of Public Health found that South Asians are particularly prone to storing fat around the liver and pancreas, leading to insulin resistance even at lower body weights². This means your “skinny” uncle could have the same metabolic problems as someone who weighs 50 pounds more from another ethnic background.

Add our traditional high-carb diet (rice, roti, sweets) to modern sedentary lifestyles, and you’ve created the perfect storm. The World Health Organization now recognizes that standard BMI cutoffs don’t apply to Asian populations, recommending lower thresholds for obesity and diabetes screening³.

Hidden Clues: What to Watch For in Your “Healthy” Relatives

Just because someone looks thin doesn’t mean they’re metabolically healthy. Here are the warning signs that your skinny uncle (or you) might be TOFI:

Physical Clues:

- Belly fat that’s disproportionate to overall body size

- Frequent fatigue, especially after meals

- Difficulty losing weight despite eating less

- Family history of diabetes or heart disease

- Skin darkening around the neck or armpits (acanthosis nigricans)

Lifestyle Red Flags:

- Late dinners (after 9 PM) followed immediately by sleep

- Diet heavy in refined carbs (white rice, naan, sweets)

- Minimal strength training or muscle-building exercise

- High stress levels from work or family pressures

- Poor sleep quality or irregular sleep patterns

The Numbers That Matter: Many doctors still rely on basic cholesterol and BMI, but these tests can miss TOFI completely. According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, South Asians need more comprehensive screening⁴.

5 Tests Every “Skinny” South Asian Should Ask For:

- Waist-to-Hip Ratio (DIY at home) – More telling than BMI

- HbA1c – Shows blood sugar control over 3 months

- ApoB – Counts dangerous cholesterol particles, not just amount

- Triglycerides – Often elevated in TOFI, especially after carb-heavy meals

- Insulin Level – Can reveal insulin resistance before diabetes develops

These tests can expose metabolic problems years before symptoms appear, giving you time to prevent heart disease rather than just treat it.

What You Can Do About TOFI

The good news? TOFI is largely reversible with the right approach. Unlike genetics, this is something you can actually change.

Rethink “Healthy” Weight: Stop assuming thin relatives are automatically healthy. Encourage comprehensive metabolic testing, especially if there’s family history of diabetes or heart disease. A normal BMI with a large waist circumference is a red flag that needs attention.

Strategic Diet Changes:

- Reduce refined carbohydrates gradually – swap white rice for brown, limit sweets to special occasions

- Time your carbs earlier in the day when insulin sensitivity is higher

- Add protein and fiber to every meal to slow sugar absorption

- Stop eating 3 hours before bedtime to improve insulin sensitivity

Exercise for Metabolic Health: Walking is great, but it’s not enough to reverse TOFI. South Asians need strength training to build muscle mass and improve insulin sensitivity. Even 20 minutes of bodyweight exercises three times per week can make a dramatic difference in how your body processes food.

Address Hidden Stress: Chronic stress raises cortisol, which promotes visceral fat storage. This is especially relevant for South Asian immigrants dealing with cultural adaptation, family expectations, and work pressures. Meditation, adequate sleep, and stress management aren’t luxuries – they’re metabolic necessities.

Get Serious About Sleep: Poor sleep disrupts hormones that control hunger and fat storage. Late dinners followed by late bedtimes create a perfect environment for TOFI development.

Time to Look Under the Hood

The conversation around South Asian health needs to evolve beyond weight and appearance. Your skinny uncle in Mumbai might need more urgent health intervention than his overweight neighbor. The cousin who “eats whatever she wants and stays thin” might be developing insulin resistance that will catch up with her in a few years.

It’s time we stopped confusing weight with wellness and started looking under the hood. Being thin is not a free pass to ignore metabolic health, especially for South Asians who face unique genetic and cultural risk factors.

The TOFI phenomenon affects millions of South Asians worldwide, but knowledge is power. By understanding how our bodies work differently, getting the right tests, and making targeted lifestyle changes, we can prevent the heart attacks and diabetes diagnoses that seem to come “out of nowhere.”

Your family’s health story doesn’t have to follow the same script as previous generations. Start the conversation today – because the life you save might be that of your seemingly healthy, skinny uncle.

Ready to assess your own risk? Take our [South Asian Heart Risk Quiz] to get a personalized risk assessment in just 2 minutes.

Share this article with family members who think being thin means being healthy – it might be the wake-up call they need.

References:

¹ The Lancet – Diabetes and cardiovascular disease in South Asians: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)31493-X/fulltext

² Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health – Ethnic differences in BMI and disease risk: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/obesity-prevention-source/ethnic-differences-in-disease-risk/

³ World Health Organization – Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/bmi_asia_strategies.pdf

⁴ National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases – Risk factors for type 2 diabetes: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/risk-factors-type-2-diabetes

⁵ INTERHEART Study – Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in South Asians: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.705370