Maya had a heart attack at 38. Her family was shocked. She exercised regularly. She ate healthy food. Her regular cholesterol tests were always “normal.”

After her heart attack, a specialist ordered different blood tests. These tests had strange names: ApoB and LP(a). The results explained everything. Maya’s ApoB was very high. Her LP(a) was dangerously elevated.

“Why didn’t my doctor test for these before?” Maya asked. The specialist explained that most doctors only order basic cholesterol tests. But these newer tests can catch hidden heart risks that regular tests miss.

If Maya had known about these tests earlier, her heart attack might have been prevented.

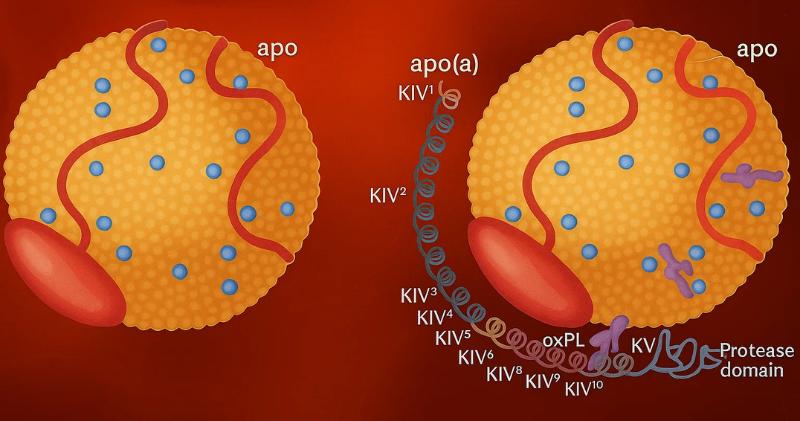

What Are ApoB and LP(a)?

These are advanced cholesterol tests with confusing names. Let’s break them down simply.

ApoB (Apolipoprotein B): Think of ApoB as a count of “bad” cholesterol particles. Regular LDL tests measure how much cholesterol is in your blood. But ApoB counts how many cholesterol particles you have.

Why does this matter? Some people have many small cholesterol particles. Others have fewer large particles. Both can show the same LDL number. But many small particles are more dangerous.

ApoB gives you the real count of dangerous particles in your blood.

LP(a) (Lipoprotein little a): This is a special type of “bad” cholesterol. LP(a) is stickier than regular cholesterol. It’s more likely to stick to artery walls and cause blockages.

LP(a) levels are mostly determined by your genes. Diet and exercise don’t change LP(a) much. You inherit high LP(a) from your parents.

Both tests help doctors see heart risks that regular cholesterol tests might miss.

Why LDL Alone Isn’t Enough

Most doctors order a basic lipid panel. This includes total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides. These tests are helpful but incomplete.

Here’s the problem with relying only on LDL:

LDL measures cholesterol amount, not particle number: Imagine two people with LDL of 120. Person A has 100 large cholesterol particles. Person B has 200 small particles. Both show the same LDL number. But Person B has double the dangerous particles.

Small particles are worse: Small, dense LDL particles slip into artery walls more easily. They cause more damage than large, fluffy particles.

LP(a) doesn’t show up in regular tests: Standard cholesterol tests don’t measure LP(a) at all. You could have very high LP(a) and never know it.

Some people have “normal” LDL but high heart risk: This happens when you have many small particles or high LP(a). Regular tests miss this completely.

Studies show that people with “normal” cholesterol can still have heart attacks. Advanced tests like ApoB and LP(a) help explain why.

Hidden Risks in South Asians

South Asians face unique challenges with these advanced cholesterol markers.

LP(a) is more common in South Asians: Research shows that up to 1 in 5 South Asians have high LP(a) levels. This is higher than most other ethnic groups.

We have more small, dense LDL particles: Even with “normal” LDL numbers, South Asians often have more dangerous small particles. ApoB testing catches this pattern.

Family history is strong: If your parents or siblings had early heart disease, you might have inherited high LP(a). This genetic risk doesn’t change with diet or exercise.

We develop heart disease younger: South Asians get heart attacks 10 years earlier than other groups. Advanced testing helps explain why this happens.

Traditional risk calculators underestimate our risk: Most heart risk calculators were designed for Western populations. They often show “low risk” for South Asians who actually have high risk.

Real example: Ravi had normal LDL but high ApoB and LP(a). His 10-year heart risk calculator showed 5% risk. But with advanced markers, his true risk was closer to 20%.

These tests help doctors see the full picture of heart risk in South Asians.

Did You Know? LP(a) is genetic and affects up to 1 in 5 South Asians. Unlike regular cholesterol, you can’t lower LP(a) with diet or exercise. It’s determined by genes you inherit from your parents. This makes testing even more important for South Asian families with heart disease history.

Should You Ask for These Tests?

Not everyone needs ApoB and LP(a) testing. But certain people should definitely ask for them.

You should consider these tests if you have:

- Family history of early heart disease (before age 55 in men, 65 in women)

- “Normal” cholesterol but other heart risk factors

- Family members with very high cholesterol

- Previous heart problems despite “good” cholesterol numbers

- Strong family history of stroke

These tests are especially important for South Asians because:

- We have higher rates of LP(a)

- We develop heart disease at younger ages

- Regular risk calculators often underestimate our risk

- Family history of heart disease is common in our community

When to ask: Discuss these tests at your next doctor visit. Bring this article with you. Ask: “Should I get ApoB and LP(a) tests given my family history?”

Cost considerations: These tests cost more than basic cholesterol panels. Insurance might not always cover them. But the information can be life-saving. One test result lasts for years since LP(a) doesn’t change much.

Interpreting Your Numbers Simply

If you get these tests, here’s how to understand your results:

ApoB (Apolipoprotein B):

- Optimal: Less than 90 mg/dL

- Near optimal: 90-119 mg/dL

- High: 120 mg/dL or higher

Think of ApoB as your “bad particle count.” Lower numbers are better.

LP(a) (Lipoprotein little a):

- Normal: Less than 30 mg/dL (or less than 75 nmol/L)

- Borderline high: 30-50 mg/dL

- High: More than 50 mg/dL (or more than 125 nmol/L)

LP(a) results might be reported in different units. Ask your doctor to explain which units they’re using.

What if your numbers are high?

- High ApoB: Usually treated with statin medications, similar to high LDL

- High LP(a): Harder to treat with regular medications. Your doctor might recommend more aggressive treatment of other risk factors

Important note: These are general ranges. Your doctor will interpret results based on your overall health picture.

Action Steps

Take charge of your heart health with these specific steps:

Ask your doctor for ApoB and LP(a) if you have family history: Print this article and bring it to your appointment. Say: “Given my family history, should I get these advanced cholesterol tests?” Be specific about which relatives had heart problems and at what age.

Keep copies of your lab results: Create a health folder at home. Keep copies of all blood test results. This helps you track changes over time and makes it easier when you see new doctors.

Learn your target ranges: Write down your numbers and target ranges. For ApoB, aim for under 90. For LP(a), under 30 is ideal. Knowing your numbers helps you stay motivated.

Share results with family members: If you have high LP(a), tell your siblings and children. They might need testing too since LP(a) is genetic. This information can save lives in your family.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My regular cholesterol is normal. Do I still need these tests? A: If you have family history of early heart disease, yes. These tests can find hidden risks that regular cholesterol tests miss. Many people with “normal” cholesterol still have heart attacks due to high ApoB or LP(a).

Q: Can I lower LP(a) with diet and exercise? A: Unfortunately, no. LP(a) is determined by genetics. Diet and exercise don’t change LP(a) levels much. However, keeping other risk factors low becomes even more important if you have high LP(a).

Q: How often should I retest ApoB and LP(a)? A: LP(a) rarely changes, so testing once is usually enough. ApoB can change with treatment, so your doctor might retest it every 6-12 months if you’re on medication.

References

- Nordestgaard, B.G., et al. (2010). Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status. European Heart Journal, 31(23), 2844-2853.

- Sniderman, A.D., et al. (2019). Apolipoprotein B particles and cardiovascular disease: a narrative review. JAMA Cardiology, 4(12), 1287-1295.

- Tsimikas, S. (2017). A test in context: Lipoprotein(a): diagnosis, prognosis, controversies, and emerging therapies. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 69(6), 692-711.

- Anand, S.S., et al. (2000). Risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease among Aboriginal people in Canada. The Lancet, 356(9228), 279-284.

- National Lipid Association. (2019). Advanced lipoprotein testing and subfractionation are clinically useful. Journal of Clinical Lipidology, 13(4), 519-525.

If this helped you, please share it with someone you love.